Assessing lung cancer risk-reduction potential of smoke-free alternatives

Smoking is the primary risk factor for developing lung cancer. Despite this, assessing a person’s risk of lung cancer is complicated. The disease is often diagnosed only after decades of smoking and even when a person does quit, the risk of lung cancer decreases slowly, not all at once. And what if a person doesn’t quit, but chooses to replace their cigarettes with an alternative to smoking? For example, a smoke-free product: one that doesn’t burn tobacco and thus produces significantly lower levels of harmful chemicals. How does that affect their risks compared with smoking or quitting?

For now, it seems like only long-term studies can provide quantitative answers to the risk-reduction potential of smoke-free products once they’re on the market and already used by many people. The sooner it can be determined that a product is better than cigarettes, the sooner adult smokers who would otherwise continue to smoke can be encouraged to switch to it. But is there a faster way to estimate the risk-reduction potential of smoke-free products?

Screenshot of the publication, which is open access and available to download for free at the publisher’s website. Published in Internal and Emergency Medicine in February 2019.

Assessment of risk-reduction potential via new approach

In this peer-reviewed publication, we propose a new approach to the assessment of the lung cancer risk-reduction potential of smoke-free products. This mechanistic approach is based on the principles of systems toxicology, following the causal chain of events that leads from smoking to disease development.

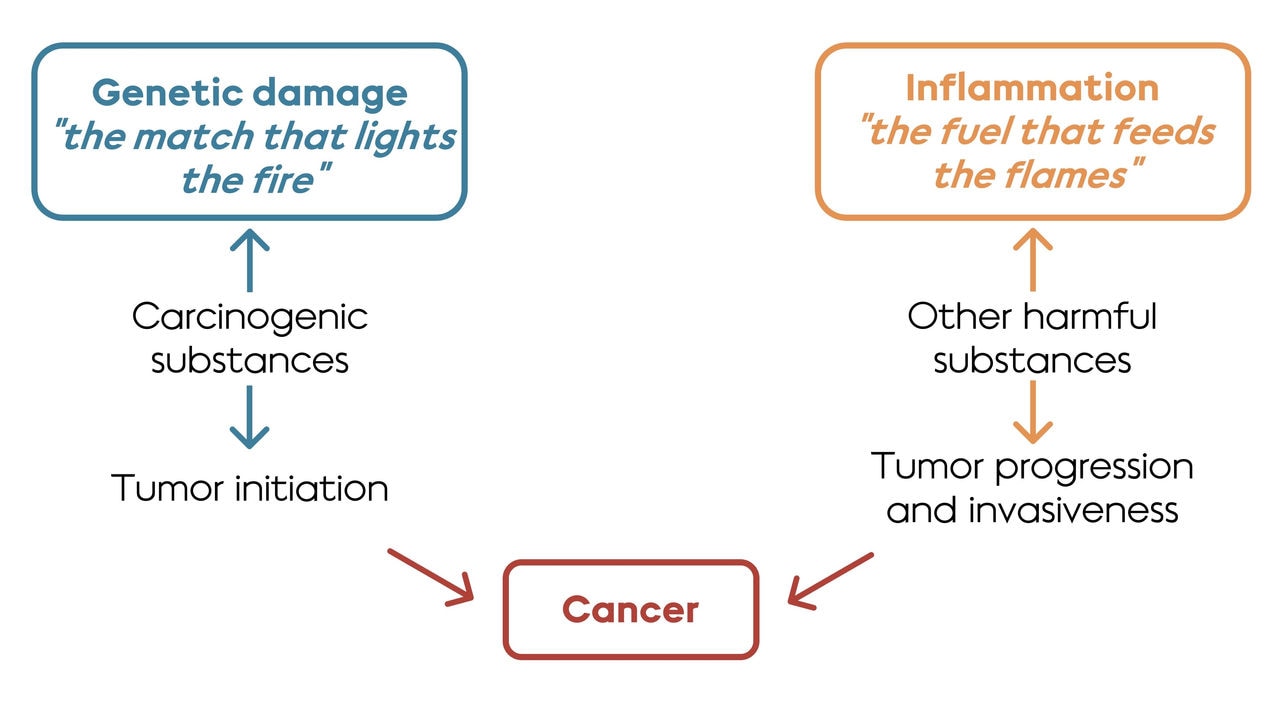

Lung cancer doesn’t have just a single cause. Exposure to carcinogens from cigarette smoke or from the environment may lead to genetic damage, which can initiate tumor growth. Exposure to harmful chemicals in general can lead to inflammation, and some types of inflammation play a major role in invasion, progression, and metastasis of tumors. These aspects, over time, can lead to lung cancer.

Ultimately, three questions must be answered if we want to assess the lung cancer risk-reduction potential for a smoke-free product compared with cigarettes.

Does switching from cigarettes to the smoke-free product:

- Reduce genetic damage?

- Reduce inflammation?

- Reduce the risk of lung cancer in laboratory models?

These questions can be answered using a combination of studies which cover aerosol chemistry, cell culture samples, in vivo disease models, systems toxicology approaches, and clinical studies. Importantly, these questions can be answered before a product is widely available, not years or decades later, giving us an earlier indication of a product’s lung cancer risk-reduction potential. If evidence supports an answer of “yes” to these three questions, it is reasonably likely that switching from cigarettes to the product in question would reduce the risk of lung cancer.

Assessment scheme, adapted from Hoeng et al (2019), with quotes from Balkwill & Mantovani (2001). Exposure to cigarette smoke (and the carcinogens and other chemicals therein) leads to genetic damage and to inflammation. Both genetic damage and inflammation contribute to the development of cancers like lung cancer.

Remaining challenges to consider

Here comes the caveat. Cell culture systems aren’t as complex as the human body, and studies that look at rodent cells don’t always accurately represent what happens in a person. In addition to that, every smoke-free product is different. These kinds of studies all have their drawbacks, which is why we propose an approach that integrates multiple different lines of study. It is the totality of evidence that should be considered when studying the risk-reduction potential of a smoke-free product.